This autumn, ‘Printing R-Evolution’, an exhibition at Venice’s Museo Correr, shines fresh light on a time when new technology transformed Europe. The media revolution that followed Gutenberg’s invention of modern printing was chaotic and multi-stranded, affecting all levels of society. Some of the changes are analogous to the ‘disruptions’ that new technology has forced upon contemporary life in the wake of the World Wide Web.

A team led by Oxford professor Cristina Dondi has applied new methods of research to a historical period cloaked in myth and mystery. Her exhibition shows that late fifteenth-century Venice was a hotbed of entrepreneurial and experimental activity, with print shops churning out a wide variety of books on subject matter embracing elementary grammar (the most popular item), astrology, commerce and wine-making. Dondi points out the four vital elements that made Venice an important hub for the book: entrepreneurs open to new ideas; skilled, innovative printers; wealthy families prepared to invest; and international trade. Venice was the Silicon Valley of its day.

Printing with moveable type accelerated literacy, education and the creation of a shared cultural heritage; it became a ‘cornerstone of European identity.’ The revolution that began with Gutenberg’s Bible (ca. 1455) in Mainz, Germany, spread quickly throughout Europe. Gutenberg printed from blackletter type, however, which was not easily understood outside Germany; from the 1460s Italian printers began using the more familiar Roman type, which could be read throughout Europe.

Over two generations, printed books superseded hand-made books. Prices plummeted. For example, in 1457 a ‘book of hours’ was sold in Florence for 10 ducats (1240 soldi). Within a decade or two, prices for similar books dropped to as little as 4 soldi (a price drop of more than 95 per cent!).

For these new printer/publishers paper became the most expensive component of the enterprise. As more people learned to read, the book trade boomed. Dondi explains that Europe was ‘awash’ with millions of books.

Around 450,000 volumes survive from this era, located in approximately 4000 libraries worldwide. The high-tech paper trail of these ‘incunabula’, as printed books from 1455-1500 are known, is at the core of Dondi’s research.

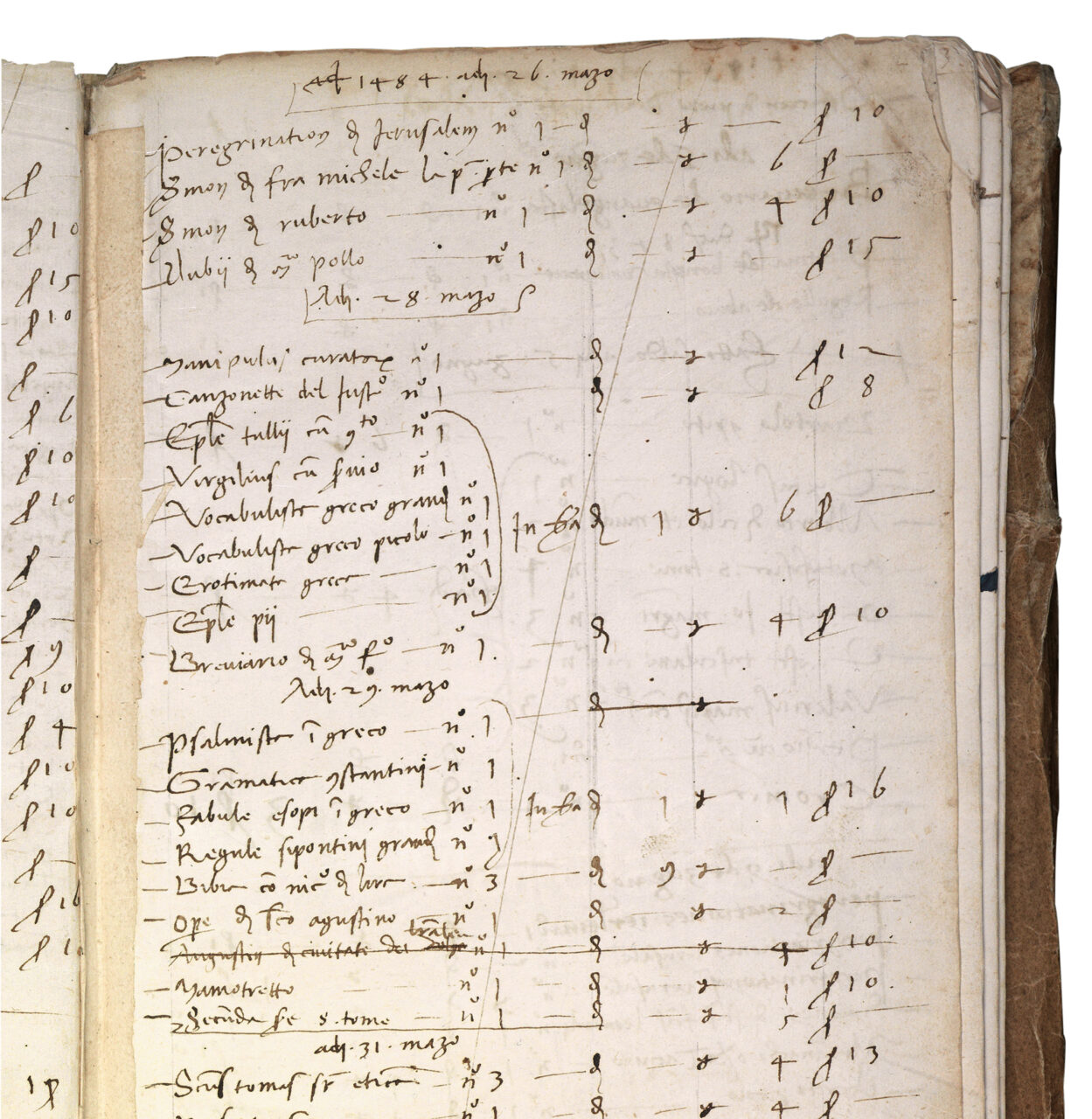

Her work began twenty years ago when cataloguing incunabula in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. She began to compile a database that showed how the books had travelled, what they cost and who paid for them, extending the search to books in other cooperating libraries. The turning point in her project was the close study of the Zornale, a unique written record of the daily activity and sales of a Venetian bookshop in the 1480s, with titles and prices for 25,000 printed books.

By following the money, Dondi realised that she could examine the incunabula period in an entirely new light. For example, she thinks it is a mistake to place too much emphasis on the celebrated publisher Aldus Manutius (see Pulp 08), whose business co-existed with at least another 200 Venetian printers. Her intense research has been fuelled by a desire to redress the balance between the star craftsmen and the anonymous printers; between the exquisite and the everyday. Her project – titled 15cBooktrade – seeks to understand more fully the scale and success of publishing in 1500, when there were millions of books in circulation.

Apart from de-canonising Manutius, she is also keen to refute the misconception that the Catholic Church stomped on printing in the days before Luther and the 1517 Reformation. Dondi’s research shows that the Church was in favour of printing: there were nuns that printed, and Bibles were produced in all the vernacular languages, including Italian, Dutch, Catalan, French and Czech.

However the most popular books were useful and secular: a typical bestseller was a psalter that taught children to read. Because such books were inexpensive and much used, they have not always survived or been preserved in the manner of more precious ‘elite’ publications. A list of books in the library of Leonardo da Vinci (1442-1519) offers an example of the wide range of printed matter available then.

The strength of Dondi’s arguments comes from the weight of numbers. Her initial Bodleian studies dealt with 7000 books. When the European Research Council (ERC) gave support to 15cBooktrade in 2013 she was able to coordinate efforts across 360 libraries worldwide, so that the database covered 40,000 books. By tracking the circulation of books, the project has also reconstructed libraries that have been dispersed.